Joe Casey wants us to wake up. He’s screaming in our ears. “Hey, fuckheads! Put it together!” For some, a rude awakening. For me, a welcome cry.

I never enjoy being the “all comics suck, especially the cape ones” guy, yet, at times, I slip into that mindset (especially if I’ve read Fear Itself). I join the crew of the hyper-critical, and we chant via our internet connections of how much we hate everything. Actually, I lied. Sometimes that mindset feels splendid. There’s a certain air of “above it all” that comes with the hate. You feel ahead of the curve. At least, I do. At some point though, you realize the amount of negativity you spout and things turn dark. You look at yourself in the reflection of your computer screen and beg the question: am I negative for a justified reason or am I hating to hate?

The “all super hero comics suck” label seems too easy to apply. It goes beyond the reasonable complaint of limited creativity to levels of nothing is possible in the genre. Sure, the genre has its problems. Creators get fucked, progress isn’t always made, and comics resemble product rather than art. The corporate lock down and fan culture provide plenty of reason for people to disown the angle. It even encourages it. Small press suffers the same issues, though. TokyoPop completely fucked Brandon Graham, the black and white boom felt more like early Image Comics than progress, and the number of publishers pushing panels of licensed properties goes uncounted. Small publishers suck just as bad. The flaws of comics go beyond the capes. It’s comics as a whole.

Still, for some, there’s nothing beyond Fantagraphics and PictureBox. The output of Oni Press doesn’t apply to them. My argument doesn’t apply to them. Whatever. For those who state an open existence though – the people in it for the art and seeing the world in open terms – it seems pretty fucking stupid to limit your reading. Sure, hero comics contain a lot of bad, and sure, few contain the passion and personal touch of art, but if any of those things were the case, super hero comics seem like the most likely place. Motherfuckers fly in these books. I’d say a lot’s possible. And – super hero comics hold a certain place in the medium. To ignore them or brush them off only signals a being living in a bubble. In some senses, cape comics are the medium, at least in terms of identity. Study that. Learn from that. Invite the cape and cowl in and let it join the house party you call context.

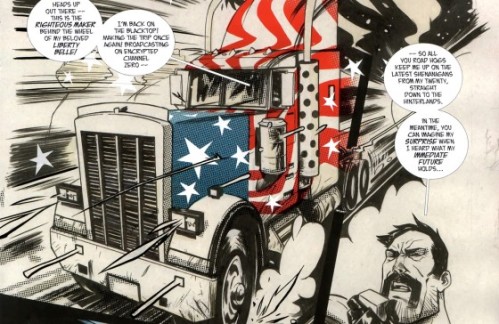

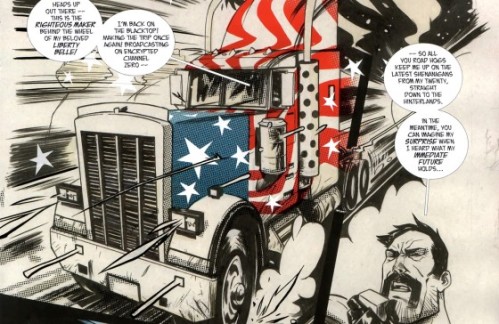

Joe Casey proves the potential and awesome of super heroes with each issue of Butcher Baker, the Righteous Maker. He sends a statement to the art house goon, the mind-mushed hero reader, and the comics professional. The super hero isn’t a bitch; the super hero has balls. Such detail is built into Casey’s lead and book namesake, Butcher Baker, as well as the up front, hyper-active aesthetic of the comic. But I wouldn’t even limit the cry to super hero comics. As typed above, small press or guys like IDW, Oni, and Dark Horse can suck just as bad. Hell, even Image who publishes the work of the industry right now publishes some shit (*cough*Invincible*cough*). As we’ve learned, it’s not about limiting one’s self to a specific area of comics or literature. The mission pertains to an all-encompassing mind, and Casey is a smart fucker. This dude speaks a little something to everyone.

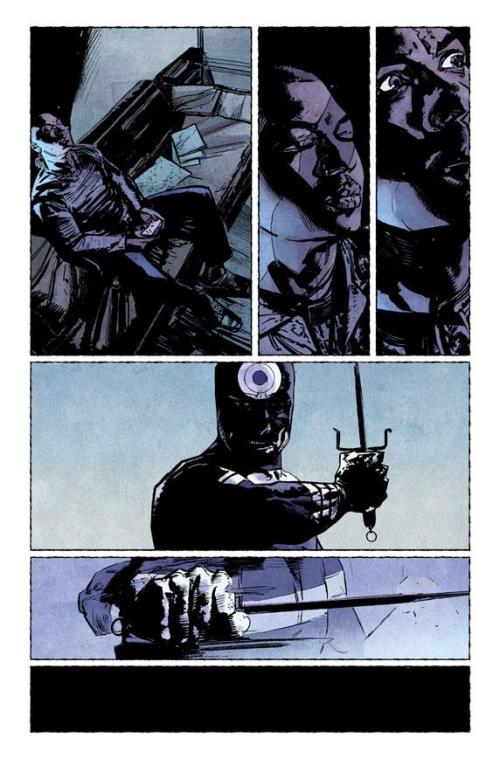

But, hey, comics books are about pretty pictures and cool looking shit. Let’s talk about the bitchin’ work of Mike Huddleston.

So much happens in this comic because of Huddleston. Casey inspires the work and sprinkles in the bits of manifesto and meta, but Huddleston sings the fucking song. His art spotlights many approaches, techniques, and tones to create an air of sophistication and complexity. Baker is not a comic to sit and stare at a consistent color choice or line. Huddleston flashes between neon and grainy black and white. Speed lines touched by a manga flare decorate fight scenes. Cross hatches and angles bend lines to an edge. My descriptions of art only go so far, but you get the idea. Mike Huddleston fills Butcher Baker with a mixture of approaches. The question to ask: why?

When reading comics (or any type of literature), always ask why things are done the way they are. That’s basic 9th grade shit, but it works. Techniques and narrative choices spawn from more than just accident. Everything contains a purpose. In the case of Huddleston’s art, I’m sure there are numerous – NUMEROUS – reasons. The dude no doubt possesses more brain cells than I, so I’m certain his artistic choices run deep. Too much happens in Baker in terms of visual expression for there not to be detailed reasons. I believe I can offer one, measly, bullshit reason, though. Huddleston’s art is on the constant move. Every scene works under different circumstances, and while I’m certain each scene looks the way it does for a specific purpose, I’m more interested in the general idea of change or the simple notion of complexity.

Casey shines a spotlight, aiming the bright, phosphorescent bulb on the super hero and the genre’s ability to preform. From that, we’re seeing the genre’s multifunction. Casey’s telling a high octane, “last job” thriller, but he’s also documenting a very personal journey. Much of this book is Casey’s career in comics deployed through the Butcher Baker analog. At the same time, the book offers character study. The old war hero forced back to the life of combat. How’s that work? Butcher Baker, mentioned in this blog post’s title, also presents statement, a manifesto from Casey communicated through the genre and comic book as media. The comic book as media … yeah. The spotlight, the statement, the study … it’s on the super hero, but again, no limits, Casey shows us the multifunction of comic books. Comic books in general, as form, rather than keeping to one section. A lot of change and movement exists in that goal. It only makes sense Huddleston’s art be so shifting. At least, in a collaborative sense. The artwork echos the writing. Provides emphasis. Huddleston’s complexity in style and technique is the visual hand to the face to push the idea through the eyeballs. Casey says comic books can do it all, and Huddleston backs him up.

Most comics keep to the single, visual vision. Reasons vary. Mostly, it rests on creative restriction because of risk of readers freaking the fuck out. Readers lose shit when comics lack realism, resemble manga, or go black and white. Huddleston brings all of that, though. He tells the notion of drawing “house style” to fuck itself. “House style” doesn’t know. It wants a set visual when comics could present so much more. The “so much more” never sees the light of day, though. The need to satisfy “house style” mentality boils strong, so artists force out status quo images. The art of Butcher Baker represents a sexy middle finger, and it yells at everyone, “hey, get a fucking load of this!” A load of what, you ask? Metaphorical testicles communicated by the artwork’s aesthetic. Simply said, Huddleston’s work is pumped full of testosterone, and it follows Casey’s lead in that comics know no bounds.

The statement of Butcher Baker matters, and a main feature of that equals Casey’s personal touch. Baker feels like a very cathartic work of fiction. We have some knowledge of the bullshit Casey’s dealt with in recent years. DC rewrote a few Superman/Batman scripts, and this obviously affected him. Maybe other things have happened as well. But the DC incident is the public one we, or I, know, and, you what, it’s enough to inspire the self-therapy Casey’s exploring. Baker contains a specific timeline, and it can be traced to match the experience of a comics writer. Issue #4 depicts a younger Butcher Baker – in his prime, the super hero of legend – combating against a villain in the middle of a desert. As the fight romps on, dialogue appears:

Butcher: “This place … kinda’ like the Wild West, eh Gator?”

“You think you can hide out, but it’s still Cowboys an’ Indians …”

“… while the goddamn world ends all around us.”

The Wild West. Cowboys an’ Indians. A good way to describe comic books, right? A medium with such potential and so much room for a pioneer to work with, but really it’s chained down by industry standards to play out the same old fights, over and over. Butcher speaks of the world ending as well. I take that as, “you can try to hide out in comics, doing something important, but while you play what’s really a dumb game, real shit is happening in the world.”

Gator is put down by page 2. Butcher than hands his mask over to an army officer and walks away from the scene.

Butcher: “Chasing super-villains halfway across the globe had me feeling like I was trapped in a Roadrunner Cartoon …”

I feel the line speaks for itself.

Issue #1 would be where we first meet up with Butcher in the present, years after the flashback. He’s living in his grotto, banging multiple chicks, and drinking. The dude’s all over the fruits of retirement. Then come Jay Leno and Dick Chaney, whom could easily be interpreted as Marvel and DC as well as other things. But for the sake of the point I’m on, let’s stick with Marvel and DC. These guys bring Butcher out of retirement to fulfill a mission. The mission, blowing up a high security prison in order to kill a bunch of super villains, goes wrong and Butcher is left with a mess to clean up. The mess being a number of old foes such as a behemoth named “Angerhead” who spouts lines like, “My hatred will fuck you up!” Even though higher powers sent Butcher on this mission, he’s on his own to clean the mess. Hell, the high powers look to cover their asses and send in military force to fuck Butcher. There’s even missiles sprayed painted with the phrase “fuck you” fired at the Righteous Maker.

This reads like an account of a comics writer picking up mainstream work and then realizing the mess it can be. Some creators claim to do very well under corporate structure. Guys like Brian Bendis has flourished and still produce solid work while being the company name. The other half of the story exists, though. Casey would most likely be the poster child. Lines like, “Those assholes promised I had their ‘full support’ on this mission – is this what they meant? The first sign of trouble…they turn their guns on me, too!?” totally fit Casey.

“But it never fails. The white men in their black suits…they want what they want. And I’m expendable. Fuck me.”

It’s like the reaction of a writer going in, trying something exciting under a corporate umbrella, and then discovering the company men are pissed and will fuck you hard to fix what you’ve done. This element of the story actually provides an interesting contradiction. As typed, most of this book sets a goal to present the awesome and capability of super-heroes as genre. It’s almost like a pep rally in comic book form. So why show the darker side? I believe it’s to discuss the issue of super-hero comics entirely. As we all know, creator rights have once again become the big, controversial issue in our daily Twitter feeds. And you know what? Good of those people concerned. It’s an issue that demands dealing. But as we all come to question the moral behavior of our heroes’ homes (the publishers), we reach a point of contradiction. We all favor creator rights, and I bet quite a few would give an arm to get Kirby is rightful due, but when you boil down the argument, how many can actually boycott Marvel? A sense of evil and moral question disgusts us, but we also love the story potential of capes. We reach a point of enternal struggle. What do we do here?

Baker’s at the same point. The dude wants to enjoy the life but constantly suffers from its seedy side. He is us, and he is Casey, locked in a world of indecision and contradiction, trying to make any fucking sense of it he can.

And then Butcher makes a break for it after a bloody battle in Times Square. He disappears like a criminal after a successful heist, beaching himself in a resort spa. Not the place for Butcher. The dude can’t escape the thoughts of heroing and who he is. Butcher contemplates what’s next for him.

The writer cannot just leave the field even after a hard fucking. The writer has to produce. It’s who the writer is. Resort beaches and bullshit small talk are not him. But what else is there other than the game he’s already played? Same goes for the reader. Once you see the potential of comics, how can you leave forever?

Butcher Baker sees a lot of time as an analog character, and honestly you could probably spend a few hundred words or more discussing analog characters in this comic. The entire cast of villains thus far seem to each speak a specific personality, and there is as well Arnie B. Willard. This determined, beer-gut of a law man comes as a bit more difficult to pin down. I’d say he represents another side of Casey, though. Just because of his ying/yang connection to Butcher. Issue #5 really gives me that vibe. When the transgender force of universe provides Willard with a higher sense, his thoughts and Butcher’s intertwine. Both characters take a trip to each other’s head, and it’s from this we learn Willard wants to be Butcher. He’s the law man who loves dishing out justice and hates his fat fuck of a wife, and Butcher appears appealing by way of his many female friends and beefy, Liberty Belle truck. It’s all in this head trip process as Casey writes in an Alan Moore image/caption juxtaposition.

The important fact would be Willard’s action of chasing Butcher. He’s chasing him to lay down the law, but his transgender friend offers a little more insight. She (or he) claims Willard must seek the ultimate truth, and from the pages in the comic it seems the ultimate truth lies with Butcher Baker. So, if Willard does represent some side of Casey, what is it that Casey finds in Butcher Baker, which I would say is another piece of him?

Willard could even fit the contradiction theme. A lawman hunting a vigilante, yet he secretly desires to be just like him.

The answer is where this series is going.

Now how the fuck do I wrap this up? I suck at conclusions. (you may even think I suck at writing. period.)

It’s like this: comics can do a lot. We live in an era of Hollywood R&D and formula. Comic books sit in the shopping carts of suits and then meet check out upon option. Nobodies’ taking it seriously until it hits the silver screen. Nobody. Except for Joe Casey and Mike Huddleston, two dudes on a mission to prove the comic book’s versatility and creative potential. Butcher Baker, the Righteous Maker contains a mix of levels and “abouts.” It’s a comic book that’s proud to be a comic book, and it’s doing things only comic books can do. In a collaborative manner, I might add. The book even teaches a lesson for the already comic book faithful. More is possible, and super heroes, the go-to blemish of the medium, can transform and do new things while offering personal expression. For some, the manifesto may not be even be enough, but remember, this series is 5 issues old, and Joe Casey seems totally open to change. I’m sure Butcher Baker will develop with the time as well as develop with its author’s voice. This would be the last comic book I’d expect to go stale.

It’s the best motherfucking book out there.

This is an early work from Elliott and Grist, but in some ways it feels like years and years of experience were on hand when they made the stories within Absent Friends. These comics are well crafted, and while printed in black and white, Grist makes use of the line art to sell the heart of these stories. More importantly, Absent Friends made me consider the role of line art. I tend to think it’s job is simply style and obviously building shapes, but there is more to it, especially when you read a comic book that takes advantage of it. Color will always be the dominate messenger of tone, certainly, but I think next time I read a comic I’ll study the line and see if it too is sending a message.

This is an early work from Elliott and Grist, but in some ways it feels like years and years of experience were on hand when they made the stories within Absent Friends. These comics are well crafted, and while printed in black and white, Grist makes use of the line art to sell the heart of these stories. More importantly, Absent Friends made me consider the role of line art. I tend to think it’s job is simply style and obviously building shapes, but there is more to it, especially when you read a comic book that takes advantage of it. Color will always be the dominate messenger of tone, certainly, but I think next time I read a comic I’ll study the line and see if it too is sending a message.